Tags

Alfred the Great, Æthelwulf of Wessex, Charles the Bald, Educational Reforms, King of the Anglo-Saxons, King of the West Saxons, King of Wessex, King of West Francia, Kingdom of Mercia, Osburh, The Danelaw, William the Conqueror

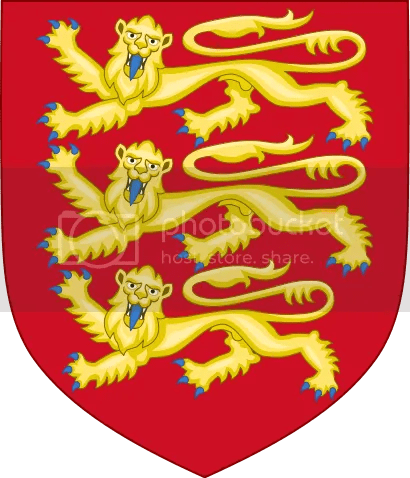

Alfred the Great (848/49 – October 26, 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to c. 886 and King of the Anglo-Saxons from c. 886 to 899. Under Alfred’s rule, considerable administrative and military reforms were introduced, prompting lasting change in England.

Alfred was a son of Æthelwulf, King of Wessex, and his wife Osburh. According to his biographer, Asser, writing in 893, “In the year of our Lord’s Incarnation 849 Alfred, King of the Anglo-Saxons”, was born at the royal estate called Wantage, in the district known as Berkshire (which is so called from Berroc Wood, where the box tree grows very abundantly).”

This date has been accepted by the editors of Asser’s biography, Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge, and by other historians such as David Dumville and Richard Huscroft. However, West Saxon genealogical lists state that Alfred was 23 when he became king in April 871, implying that he was born between April 847 and April 848. This dating is adopted in the biography of Alfred by Alfred Smyth, who regards Asser’s biography as fraudulent, an allegation which is rejected by other historians.

Alfred was the youngest of six children of Æthelwulf, King of Wessex, and his wife Osburh. His eldest brother, Æthelstan, was old enough to be appointed sub-king of Kent in 839, almost 10 years before Alfred was born. Æthelstan died in the early 850s. Alfred’s next three brothers were successively kings of Wessex. Æthelbald (858-860) and Æthelberht (860-865) were also much older than Alfred, but Æthelred (865-871) was only a year or two older.

Alfred’s only known sister, Æthelswith, married Burgred, King of Mercia in 853. Most historians think that Osburh was the mother of all Æthelwulf’s children, but some suggest that the older ones were born to an unrecorded first wife.

Alfred’s mother was Osburga, daughter of Oslac of the Isle of Wight, Chief Butler of England. Asser, in his Vita Ælfredi asserts that this shows his lineage from the Jutes of the Isle of Wight. This is unlikely because Bede tells us that they were all slaughtered by the Saxons under Cædwalla.

Osburh was described by Alfred’s biographer Asser as “a most religious woman, noble by temperament and noble by birth”. She had died by 856 when Æthelwulf married Judith, daughter of Charles the Bald, King of West Francia.

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of a Mercian nobleman, Æthelred Mucel, Ealdorman of the Gaini. The Gaini were probably one of the tribal groups of the Mercians. Ealhswith’s mother, Eadburh, was a member of the Mercian royal family.

They had five or six children together, including Edward the Elder who succeeded his father as king; Æthelflæd who became lady of the Mercians; and Ælfthryth who married Baldwin II, Count of Flanders.

Osferth of Wessex was described as a relative in King Alfred’s will and he attested charters in a high position until 934. A charter of King Edward’s reign described him as the king’s brother – mistakenly according to Keynes and Lapidge, and in the view of Janet Nelson, he probably was an illegitimate son of King Alfred.

After ascending the throne, Alfred spent several years fighting Viking invasions. In 868, Alfred was recorded as fighting beside Æthelred in a failed attempt to keep the Great Heathen Army led by Ivar the Boneless out of the adjoining Kingdom of Mercia. The Danes arrived in his homeland at the end of 870, and nine engagements were fought in the following year, with mixed results; the places and dates of two of these battles have not been recorded.

In April 871 King Æthelred of Wessex died and Alfred acceded to the throne of Wessex and the burden of its defence, even though Æthelred left two under-age sons, Æthelhelm and Æthelwold. This was in accordance with the agreement that Æthelred and Alfred had made earlier that year in an assembly at an unidentified place called Swinbeorg.

The brothers had agreed that whichever of them outlived the other would inherit the personal property that King Æthelwulf had left jointly to his sons in his will. The deceased’s sons would receive only whatever property and riches their father had settled upon them and whatever additional lands their uncle had acquired. The unstated premise was that the surviving brother would be king. Given the Danish invasion and the youth of his nephews, Alfred’s accession probably went uncontested.

Originally styled as “King of the West Saxons” Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Saxons from about 886, as more of England came under his rule; and while he was not the first king to claim to rule all of the English, his rule represents the start of the first unbroken line of kings to rule the whole of England, the House of Wessex.

Alfred won a decisive victory in the Battle of Edington in 878 and made an agreement with the Vikings, creating what was known as the Danelaw in the North of England. Alfred also oversaw the conversion of Viking leader Guthrum to Christianity. He defended his kingdom against the Viking attempt at conquest, becoming the dominant ruler in England. Details of his life are described in a work by 9th-century Welsh scholar and bishop Asser.

On a trip to Rome Alfred had stayed with Charles the Bald and it is possible that he may have studied how the Carolingian kings had dealt with Viking raiders. Learning from their experiences he was able to establish a system of taxation and defence for Wessex. There had been a system of fortifications in pre-Viking Mercia that may have been an influence. When the Viking raids resumed in 892 Alfred was better prepared to confront them with a standing, mobile field army, a network of garrisons and a small fleet of ships navigating the rivers and estuaries.

Alfred was known as a great reformer and his ideas were applied to the education system developed during his reign. Alfred placed considerable importance on translations from Latin to English in order to establish a wider array of books accessible for learning and intellectual pursuits.

Alfred was greatly inspired by the reforms established by Emperor Charlemagne. Afred sought to introduced court schools, which was a system providing a solid education for the nobility as well as those born with lesser status. The Anglo-Saxon King ensured the best scholars would teach in these schools, with curricula dedicated to the liberal arts. Alfred’s keen intellectual disposition was evident in the way he chose to reform, develop and improve Anglo-Saxon society under his reign.

Due to his educational reforms Alfred had a reputation as a learned and merciful man of a gracious and level-headed nature who encouraged education, proposing that primary education be conducted in Old English rather than Latin and improving the legal system and military structure and his people’s quality of life.

Alfred died on October 26, 899 at the age of 50 or 51. How he died is unknown, but he suffered throughout his life with a painful and unpleasant illness. His biographer Asser gave a detailed description of Alfred’s symptoms, and this has allowed modern doctors to provide a possible diagnosis. It is thought that he had either Crohn’s disease or haemorrhoids. His grandson King Eadred seems to have suffered from a similar illness.

Alfred was temporarily buried at the Old Minster in Winchester with his wife Ealhswith and later, his son Edward the Elder. Before his death he ordered the construction of the New Minster hoping that it would become a mausoleum for him and his family. Four years after his death, the bodies of Alfred and his family were exhumed and moved to their new resting place in the New Minster and remained there for 211 years.

When William I the Conqueror rose to the English throne after the Norman conquest in 1066, many Anglo-Saxon abbeys were demolished and replaced with Norman cathedrals. One of those unfortunate abbeys was the very New Minster abbey where Alfred was laid to rest.

Before demolition, the monks at the New Minster exhumed the bodies of Alfred and his family to safely transfer them to a new location. The New Minster monks moved to Hyde in 1110 a little north of the city, and they transferred to Hyde Abbey along with Alfred’s body and those of his wife and children, which were interred before the high altar.

He was given the epithet “the Great” in the 16th century.