Tags

2nd Duke of Buckingham, Countess of Stafford, Elizabeth Woodville, English Nobility, Henry Stafford, House of Plantagenet, House of Stafford, King Edward III of England, King Richard II of England, Kings and Queens of England, Lady Anne of Gloucester, Thomas of Woodstock

Lady Anne of Gloucester, Countess of Stafford (April 30, 1383 – October 16, 1438) was the eldest daughter and eventually sole heiress of Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester by his wife Eleanor de Bohun.

Lady Anne was born on April 30, 1383 and was baptised at Pleshey, Essex, sometime before 6 May. Her uncle, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, (third son of King Edward III), ordered several payments to be made in regards to the event. She was the granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

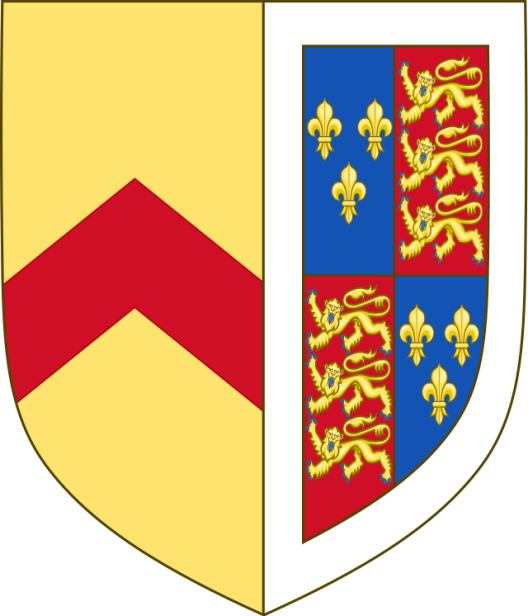

Coat of Arms of Lady Anne of Gloucester, Countess of Stafford.

Family

Father

Her father was Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester (January 7, 1355 – September 8 or 9, 1397). He was the fifth surviving son and youngest child of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault.

In 1377, at the age of 22, Thomas of Woodstock was knighted and created Earl of Buckingham. On June 22, 1380 he became Earl of Essex Jure uxoris (in right of his wife). In 1385, he received the title Duke of Aumale, and at about the same time was created Duke of Gloucester.

Thomas married Eleanor de Bohun, the elder daughter and co-heiress with her sister, Mary de Bohun, of their father Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford. Thomas of Woodstock and his wife Eleanor had:

1. Humphrey, 2nd Earl of Buckingham (c. 1381 – 1399). English peer and member of the House of Lords. Died unmarried.

2. Anne of Gloucester (c. 1383 – 1438) who married three times.

3. Joan (1384–1400), who married Gilbert Talbot, 5th Lord Talbot (1383–1419) and died in childbirth.

4. Isabel (12 March 1385/1386 – April 1402), a nun of the Order of Minoresses

Philippa (c. 1388), died young

Thomas of Woodstock was the leader of the Lords Appellant, a group of powerful nobles whose ambition to wrest power from Thomas’s nephew, King Richard II of England, culminated in a successful rebellion in 1388 that significantly weakened the king’s power. Richard II managed to dispose of the Lords Appellant in 1397, and Thomas was imprisoned in Calais to await trial for treason.

During that time he was murdered, probably by a group of men led by Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk, and the knight Sir Nicholas Colfox, presumably on behalf of Richard II. Thomas was buried in Westminster Abbey, first in the Chapel of Saint Edmund and Saint Thomas in October 1397, and two years later reburied in the Chapel of Saint Edward the Confessor. His wife was buried next to him.

As he was attainted as a traitor, his dukedom of Gloucester was forfeit. The title Earl of Buckingham was inherited by his son, who died in 1399 only two years after Thomas’ own death.

Mother

On Lady Anne’s maternal side she was also a descendant of the Kings of England.

Lady Anne’s mother was Eleanor de Bohun (c. 1366–1399) the elder daughter and co-heiress (with her sister, Mary de Bohun), of Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford (1341–1373), by his wife Joan Fitzalan, a daughter of Richard FitzAlan, 10th Earl of Arundel and his second wife Eleanor of Lancaster.

Lady Anne’s grandmother, Eleanor of Lancaster, Countess of Arundel (sometimes called Eleanor Plantagenet; 1318-1372) was the fifth daughter of Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster and Maud Chaworth.

Her great-grandfather, Henry, 3rd Earl of Leicester and Lancaster (c. 1281-1345) was a grandson of King Henry III of England (1216–1272) via his son, Edmund Crouchback, 1st Earl of Lancaster; and was one of the principals behind the deposition of King Edward II (1307–1327), his first cousin.

Marriages

Lady Anne married three times. Her first marriage was to Thomas Stafford, 3rd Earl of Stafford (c. 1368 – July 4, 1392) who was the second son—but the senior surviving heir—of Hugh Stafford, 2nd Earl of Stafford and Philippa de Beauchamp, daughter of Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick. The marriage occurred around 1390. He died on July 4, 1392. He is interred in Westminster, and was interred in Stone, with his father; his widow, Anne, with whom he had had no children, married his youngest brother Edmund Stafford, 5th Earl of Stafford.

On June 28, 1398, Anne married Edmund Stafford, 5th Earl of Stafford (March 2, 1378 – July 14, 1403). They had three children together:

1. Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, who married his second cousin, Anne, daughter of Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, and Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland. Joan was a daughter of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, and his third wife Katherine Swynford.

2. Anne Stafford, Countess of March, who married Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March. Edmund was a great-grandson of Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence (the third son, but the second son to survive infancy, of the English king Edward III and Philippa of Hainault). Edmund and Anne had no children. She married secondly John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter (d. 1447), and had one son, Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter (d. 1475), and a daughter Anne, who married John Neville, 1st Baron Neville de Raby.

3. Philippa Stafford, died young.

In about 1405, Anne married William Bourchier, 1st Count of Eu (d. 1420), son of Sir William Bourchier and Eleanor of Louvain, by whom she had the following children:

1. Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex. He married Isabel of Cambridge, daughter of Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge, and Anne de Mortimer. Isabel was also an older sister of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York.

2. Eleanor Bourchier, Duchess of Norfolk, married John Mowbray, 3rd Duke of Norfolk.

3. William Bourchier, 9th Baron FitzWarin

4. Cardinal Thomas Bourchier

5.John Bourchier, Baron Berners. John was the grandfather of John, Lord Berners, the translator of Froissart.

Lady Anne died on October 16, 1438 aged 55 and was buried in Llanthony Secunda Priory, Gloucester.

On Anne’s death, in 1438, the title of Earl of Buckingham (as well as her other titles) passed to her son Humphrey Stafford, Earl of Stafford, who in 1444 was created Duke of Buckingham by King Henry VI. his title remained in the Stafford family until the attainder and execution of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, in 1521, Anne’s great-great grandson.

As we have seen Lady Anne was not only a granddaughter of a King of England, she was related to many noble families of England, her descendants continued that trend. They were among England’s noble families as well has being related to England’s Royal Family.

Descendants

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Son

Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 6th Earl of Stafford, KG (December 1402 – July 10, 1460). Humphrey Stafford married Lady Anne Neville, daughter of Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland and Lady Joan Beaufort. Joan Beaufort (c. 1379-1440), was the youngest of the four legitimised children and only daughter of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (third surviving son of King Edward III), by his mistress, later wife, Katherine Swynford. Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, was killed during the Battle of Northampton on July 10, 1460.

Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Grandson

Humphrey Stafford (c. 1425 – c. May 22, 1458), generally known by his courtesy title of Earl of Stafford, was the eldest son of Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Lady Anne Neville (d. 1480). Stafford married Lady Margaret Beaufort, daughter of Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset and Lady Eleanor Beauchamp. By her father, Lady Margaret Beaufort, was a niece of Joan Beaufort, Queen of Scots and a cousin to Lady Margaret Beaufort (mother of King Henry VII of England). Humphrey Stafford Predeceased his father. Lord and Lady Stafford had a single son, Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham (1455–1483).

Great-Grandson

Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham (September 4, 1455 – November 2, 1483). He inherited his title, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, after his grandfather, the 1st Duke of Buckingham, was killed during the Battle of Northampton on July 10, 1460. In February 1466, at age 10, he was married to Catherine Woodville, sister of Edward IV’s queen, Elizabeth Woodville, and daughter to Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers. [I will write more on him tomorrow].

Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

Great-Great Grandson

Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham (February 3, 1478 – May 17, 1521) was an English nobleman. He was the son of Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, and Katherine Woodville, and nephew of Elizabeth Woodville and King Edward IV. Thus Edward Stafford was a first cousin once removed of King Henry VIII. Buckingham was one of few peers with substantial Plantagenet blood and maintained numerous connections, often among his extended family, with the rest of the upper aristocracy, which activities attracted Henry VIII’s suspicion.

During 1520, Buckingham became suspected of potentially treasonous actions and Henry authorised an investigation. The King personally examined witnesses against him, gathering enough evidence for a trial. The Duke was finally summoned to Court in April 1521 and arrested and placed in the Tower. He was tried before a panel of 17 peers, being accused of listening to prophecies of the King’s death and intending to kill the King. Buckingham was executed on Tower Hill on 17 May 17, 1521. Buckingham was posthumously attainted by Act of Parliament on July 13, 1523, disinheriting most of his wealth from his children.

Great-Great-Great Grandson

Henry Stafford, 1st Baron Stafford (September 18, 1501 – April 30, 1563). After the execution for treason in 1521 and posthumous attainder of his father Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, with the forfeiture of all the family’s estates and titles, he managed to regain some of his family’s position and was created Baron Stafford in 1547. However, his family never truly recovered from the blow and thenceforward gradually declined into obscurity, with his descendant the 6th Baron being requested by King Charles I in 1639 to surrender the barony on account of his poverty.