Tags

1st Earl of March, Duchy of Aquitaine, Hundred Years War, Isabella of France, King Edward III of England, King Philip VI of France, Kingdom of England, Philippa of Hainault, Roger Mortimer, Treaty of Brétigny

Edward III (November 13, 1312 – June 21, 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377.

Edward of Windsor was the son of King Edward II of England and Lord of Ireland and his wife Princess Isabella of France who was the youngest surviving child and only surviving daughter of King Philippe IV of France and Queen Joan I of Navarre.

He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after the disastrous and unorthodox reign of his father, King Edward II. King Edward III transformed the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe.

His fifty-year reign was one of the longest in English history, and saw vital developments in legislation and government, in particular the evolution of the English Parliament, as well as the ravages of the Black Death. He outlived his eldest son, Edward the Black Prince, and the throne passed to his grandson Richard II.

King Edward III was crowned at age fourteen after his father was deposed by his mother, Isabella of France, and her lover Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March. Mortimer’s G/G/G grandfather was King John of England and his G/G grandfather was Llywelyn the Great, Prince of Wales.

Mortimer knew his position in relation to the King was precarious and he unwisely subjected Edward to disrespect.

Philippa of Hainault had been engaged to Edward when he was Prince of Wales, in 1326. Philippa was the aughter of Count Guillaume of Hainault and French Princess Joan of Valois, the second eldest daughter of the French Prince Charles, Count of Valois, and Margaret, Countess of Anjou and Maine. Joan of Valois was the sister of King Philippe VI of France.

The King married Philippa of Hainault at York Minster on January 24, 1328.

At the birth of their first child, Edward of Woodstock, on June 15, 1330 it only increased tension with Mortimer. Eventually, King Edward III decided to take direct action against Mortimer. Although up until now Edward had kept a low profile, drawing little attention to himself, it is likely that he increasingly suspected that Mortimer’s behaviour could endanger Edward’s own life, as the former’s position became more unpopular.

Contemporary chroniclers suspected, too, that Mortimer had designs on the throne, and it is likely that it was these rumours that brought things to a head: both his mother and Mortimer were to go. If Sir Thomas Grey in his Scalacronica is correct, Edward hated the “rule of the Queen his mother, and hating the Earl of March [Mortimer], for the Queen did everything in accordance with him”.

Aided by his close companion William Montagu, 3rd Baron Montagu, and a small number of other trusted men, Edward took Mortimer by surprise at Nottingham Castle on October 19, 1330. Mortimer was executed and Edward’s personal reign began.

After a successful campaign in Scotland he declared himself rightful heir to the French throne, starting the Hundred Years’ War.

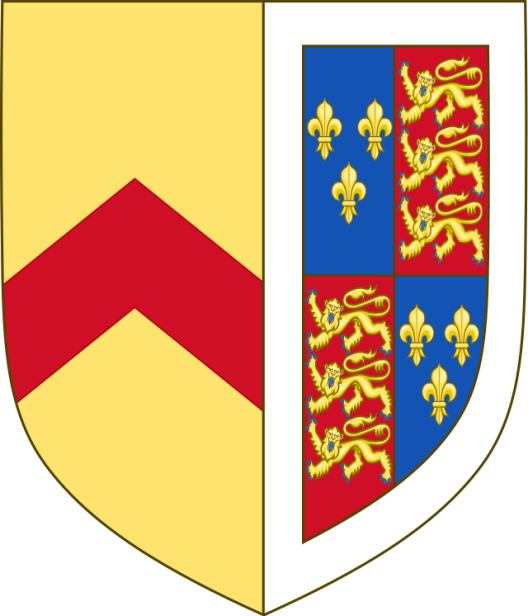

In 1337, King Philippe VI of France confiscated the English king’s Duchy of Aquitaine and the county of Ponthieu. Instead of seeking a peaceful resolution to the conflict by paying homage to the French king, as his father had done, King Edward III responded by laying claim to the French crown as the grandson of King Philippe IV of France.

The French rejected this based on the precedents for agnatic succession set in 1316 and 1322. Instead, they upheld the rights of Philip IV’s nephew Philip VI (an agnatic descendant of the House of France), thereby setting the stage for the Hundred Years’ War.

Following some initial setbacks, this first phase of the war went exceptionally well for England, and would become known as the Edwardian War. Victories at Crécy and Poitiers led to the highly favourable Treaty of Brétigny, in which England made territorial gains, and Edward renounced his claim to the French throne. Edward’s later years were marked by international failure and domestic strife, largely as a result of his inactivity and poor health.

Edward was temperamental and thought himself capable of feats such as healing by the royal touch as some prior English kings did. He was also capable of unusual clemency. He was in many ways a conventional king whose main interest was warfare, but he also had a broad range of non-military interests. Admired in his own time and for centuries after, he was later denounced as an irresponsible adventurer by Whig historians, but modern historians credit him with significant achievements.

Edward was also unpopular with the common people due to his repeated demands that they provide unpaid military service in Scotland. None of his campaigns there were successful, and this led to a further decline in his popularity, particularly with the nobility. His image was damaged again in 1322 when he executed his cousin, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, and confiscated the Lancaster estates.

Edward did not have much to do with any of this; after around 1375 he played a limited role in the government of the realm. Around 29 September 1376 he fell ill with a large abscess. After a brief period of recovery in February 1377, the King died of a stroke at Sheen on June 21, 1377.

King Edward III was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, King Richard II, son of Edward of Woodstock, since Woodstock himself had died on June 8, 1376. In 1376, Edward had signed letters patent on the order of succession to the crown, citing in second position his third son John of Gaunt, but ignoring Philippa, daughter of his second son Lionel of Antwerp. Philippa’s exclusion contrasted with a decision by Edward I in 1290, which had recognized the right of women to inherit the crown and to pass it on to their descendants.