Having considered the matter of finding a new wife for King Henry VIII, his chief minister, Thomas Cromwell suggested Anne of Cleves.

Anne was born in 1515, on either September 22, or more probably June 28. She was born in Düsseldorf, the second daughter of Johann III of the House of La Marck, Duke of Jülich jure uxoris, Cleves, Berg jure uxoris, Count of Mark, also known as de la Marck and Ravensberg jure uxoris (often referred to as Duke of Cleves) who died in 1538, and his wife Maria, Duchess of Jülich-Berg (1491–1543). Anne grew up in Schloss Burg on the edge of Solingen.

In 1527, at the age of 11, Anne was betrothed to François, the 9-year-old son and heir of Antoine, Duke of Lorraine. But because François was under the age of consent (10 years old) at the time of the arrangement, the betrothal was considered unofficial and was cancelled in 1535. Her brother Wilhelm was a Lutheran but the family was unaligned religiously, with her mother, the Duchess Maria, described as a “strict Catholic”. Her father’s ongoing dispute over Gelderland with Emperor Charles V made the family suitable allies for King Henry VIII in the wake of the Truce of Nice.

Negotiations to arrange the marriage were in full swing by March 1539. Cromwell oversaw the talks and a marriage treaty was signed on October 4, of that year. The King agreed to pay a dowry of 100,000 florins to the bride’s brother.

Wedding preparations

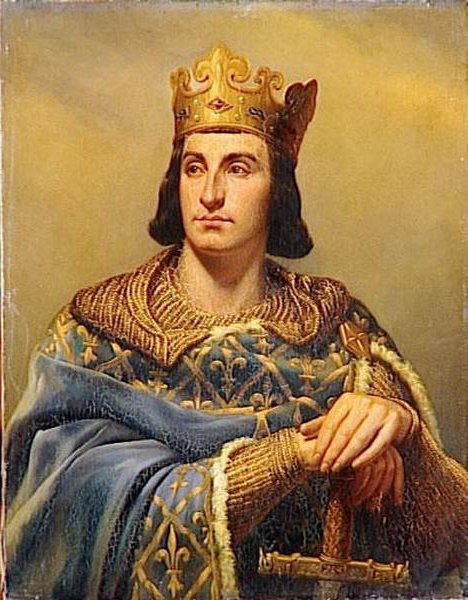

The artist Hans Holbein the Younger was dispatched to Düren to paint portraits of Anne and her younger sister, Amalia, each of whom Henry was considering as his fourth wife. Henry required the artist to be as accurate as possible, not to flatter the sisters. The portraits are now located in the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Another 1539 portrait, by the school of Barthel Bruyn the Elder, is in the collection of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Henry valued education and cultural sophistication in women, but Anne lacked these traits. She had received no formal education but was skilled in needlework and liked playing card games. She could read and write, but only in German. Nevertheless, Anne was considered gentle, virtuous and docile, which is why she was recommended as a suitable candidate for Henry.

Anne was described by French ambassador Charles de Marillac as tall and slim, “of middling beauty and of very assured and resolute countenance.” She was fair-haired and was said to have had a lovely face. In the words of the chronicler Edward Hall, “Her hair hanging down, which was fair, yellow and long … she was apparelled after the English fashion, with a French hood, which so set forth her beauty and good visage, that every creature rejoiced to behold her.” She appeared rather solemn by English standards, and looked old for her age. Holbein painted her with a high forehead, heavy-lidded eyes and a pointed chin.

Despite speculation that Holbein painted her in an overly flattering light, it is more likely that the portrait was accurate; Holbein remained in favour at court. After seeing Holbein’s portrait, and urged on by the complimentary description of Anne given by his courtiers, the 49-year-old king agreed to wed Anne.

Anne was initially to travel to England alone with her cortège – the death of her father prevented her brother and mother from travelling – but there were concerns about a beautiful, sheltered young woman who had never traveled by sea making such a journey, especially during the winter. She traveled from Düsseldorf to Cleves, and then to Antwerp where she was received by fifty English merchants.

Henry met her privately on New Year’s Day 1540 at Rochester Abbey in Rochester on her journey from Dover. Henry and some of his courtiers, following a courtly-love tradition, went disguised into the room where Anne was staying.

According to the testimony of Henry’s companions, he was disappointed with Anne, feeling that she was not as described. According to the chronicler Charles Wriothesley, Anne “regarded him little”, though it is unknown whether she knew this was the king. Henry then revealed his true identity to Anne, although he is said to have been put off the marriage from then on. Henry and Anne then met officially on 3 January on Blackheath outside the gates of Greenwich Park, where a grand reception was laid out.

Most historians believe that Henry’s misgivings about the marriage were blamed on Anne’s alleged unsatisfactory appearance and her failure to inspire him to consummate the marriage. He felt that he had been misled after his advisors had praised Anne’s beauty: “She is nothing so fair as she hath been reported”, he complained. Cromwell received some blame for the Holbein portrait, which Henry believed had not been an accurate representation of Anne, and for some of the exaggerated reports of her beauty. When the king finally met Anne, he was reportedly shocked by her plain appearance, and the marriage was never consummated.

Henry urged Cromwell to find a legal way to avoid the marriage but, by this point, doing so was impossible without endangering the vital alliance with the Germans. In his anger and frustration, the King turned on Cromwell, to his subsequent regret.

Anne of Cleves was seen as an important ally in case of a Roman Catholic attack on England, for Duke Johann III of Cleves was

between Lutheranism and Catholicism. The marriage took place in January 1540.

However, it was not long before Henry wished to annul the marriage so he could marry another. Anne did not argue, and confirmed that the marriage had never been consummated. Anne’s previous betrothal to the Duke of Lorraine’s son Francis provided further grounds for the annulment. On June 24, 1540 King Henry VIII commands, Anne of Cleves, to leave the court.

The marriage was subsequently dissolved in July 1540, and Anne received the title of “The King’s Sister”, two houses, and a generous allowance. It was soon clear that Henry had fallen for the 17-year-old Catherine Howard, the Duke of Norfolk’s niece. This worried Cromwell, for Norfolk was his political opponent.

Shortly after, the religious reformers (and protégés of Cromwell) Robert Barnes, William Jerome and Thomas Garret were burned as heretics. Cromwell, meanwhile, fell out of favour although it is unclear exactly why, for there is little evidence of differences in domestic or foreign policy. Despite his role, he was never formally accused of being responsible for Henry’s failed marriage.

Cromwell was now surrounded by enemies at court, with Norfolk also able to draw on his niece Catherine’s position. Cromwell was charged with treason, selling export licences, granting passports, and drawing up commissions without permission, and may also have been blamed for the failure of the foreign policy that accompanied the attempted marriage to Anne. He was subsequently attainted and beheaded.