Tags

King Charles III, King George III, King Henry VIII, Kingdom of England, Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Kingdom of Ireland, Kingdom of Scotland, Northern Ireland, Principality of Wales, Queen Anne, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

From the Emperor’s Desk: This is an updated and expanded article I wrote in 2012 at the start of my blog when Elizabeth II was Queen.

Elizabeth II, Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

I am a bit of a stickler for correct and proper usage of styles and titles. So it is a bit of a pet peeve of mine when these are used improperly. The main one that bugs me is calling Charles III, King of England. That bothers me because “King of England” is not his correct title! His correct title, simplified here, is King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. England has not been a separate sovereign state since 1707.

Wales

The country of Wales was once an independent Principality. The conquest of Wales by Edward I of England was completed by 1283, though Owain Glyndŵr rebelled against English rule in the early 15th century and briefly re-established an independent Welsh principality. The whole of Wales was annexed by England and incorporated within the English legal system under the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542.

Ireland

In 1166, Mac Murrough King of Leinster, had fled to Anjou, France, following a war involving Tighearnán Ua Ruairc, of Breifne, and sought the assistance of the Angevin King Henry II of England, in recapturing his kingdom.

In 1171, Henry arrived in Ireland in order to review the general progress of the expedition. He wanted to re-exert royal authority over the invasion which was expanding beyond his control. Henry successfully re-imposed his authority over Strongbow and the Cambro-Norman warlords and persuaded many of the Irish kings to accept him as their overlord, an arrangement confirmed in the 1175 Treaty of Windsor.

The invasion was legitimised by reference to provisions of the alleged Papal Bull Laudabiliter, issued by an Englishman, Pope Adrian IV, in 1155. The document apparently encouraged Henry to take control in Ireland in order to oversee the financial and administrative reorganisation of the Irish Church and its integration into the Roman Church system.

In 1172, Pope Alexander III further encouraged Henry to advance the integration of the Irish Church with Rome. Henry was authorised to impose a tithe of one penny per hearth as an annual contribution. This church levy called Peter’s Pence, is extant in Ireland as a voluntary donation. In turn, Henry II assumed the title of Lord of Ireland which Henry conferred on his younger son, John Lackland, in 1185.

This defined the Anglo-Norman administration in Ireland as the Lordship of Ireland. When Henry’s successor, King Richard I of England, died unexpectedly in 1199, King John inherited the crown of England and retained the Lordship of Ireland. The Kings of England remained Lord of Ireland until the Crown of Ireland Act 1542.

Henry VIII, King of England and Ireland

When King Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church to marry Anne Boleyn his legal claim to the lordship of Ireland was tenuous because that title had been granted by the Pope and was connected to the Roman Catholic Church. The solution to this quandary was to elevate Henry’s title from Lord to King.

By the terms of the Crown of Ireland Act 1542, the Parliament of Ireland created Henry VIII of England as “King of Ireland”. Although the Kings of England, and later the Kings of England and Scotland, we’re also Kings of Ireland, Ireland was not politically joined to England and Scotland and remained a separate independent Kingdom and was ruled in a personal union by the king or queen.

With Wales having been incorporated within the Kingdom of England, and Ireland as a separate Kingdom ruled by the English monarch, let us now focus on how the kingdoms of England and Scotland were united.

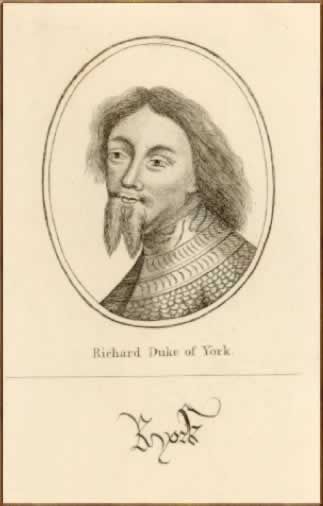

Here is a little historical background on the issue. For centuries England and Scotland were separate sovereign Kingdoms each with their own monarch. There was not always peace between the two states as England constantly tried to keep Scotland subdued. Edward I of England (1272-1307) is not known as the Hammer of the Scots for nothing!

The Kingdoms of England and Scotland ruled by separate monarchs until 1603. Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland died without issue and her closest relative that had a claim to the throne was her cousin King James VI of Scotland (1567-1625).

James I-VI, King of England, Scotland and Ireland

James VI of Scotland was deemed the rightful heir though there is debate as to whether or not Queen Elizabeth I actually named the Scottish King as her successor; he was accepted as King and became King James I of England and Ireland. There were other candidates for the English Throne besides the Scottish King, but that’s a subject for another blog entry.

The accession of the Scottish King on the English throne did not politically unite the two nations. Both Kingdoms were ruled by James but remained individual sovereign states that retained their own parliaments and laws. In England and Ireland he is reckoned as James I and in Scotland he is reckoned as James VI.

Although James I-VI liked to consider himself as the first King of Great Britain this title was self appointed and was not approved of by Parliament and the title had no legal barring.

Therefore, from 1603 until 1707 (excluding the Commonwealth period when the monarchy was abolished) the title of the monarch was King/Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland (they also called themselves the Kings of France but that is another story).

In 1707 came the Act of Union uniting the Parliaments of England and Scotland creating the new nation of Great Britain. The uniting of England and Scotland has a complex history which I have written about before on this blog, and will do a deeper dive into it at some future point.

Anne, Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland 1702-1707, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland 1707-1714

Suffice it to say, at this point England and Scotland ceased to be independent sovereign states and were then, and now, considered separate states within the union. Ireland remained separate from Great Britain and remained in personal union with the monarch.

The title of the monarch changed accordingly at this time and the titles of King or Queen of England and King or Queen of Scotland passed into history. Anne was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland when the Act of Union of 1707 was passed and her title was changed to Queen of Great Britain and Ireland.

George II, King of Great Britain and Ireland, Elector of Hanover and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

The title remained King or Queen of Great Britain and Ireland for 93 years until the nation expanded once more. The Act of Union of 1801 joined the Parliament of Ireland with the Parliament of Great Britain. Ireland was now included in the political union with Great Britain and the new state became the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

King George III (1760-1820) was the monarch at the time and his title changed accordingly. He was now King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was at this point the pretence to the title King of France was finally dropped.

George III, King of Great Britain and Ireland, Elector of Hanover and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg 1760-1801, King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, George II, King of Great Britain and Ireland, King of Hanover and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

From 1714 to 1837 the British monarch was also Elector of Hanover and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg within the German Holy Roman Empire until 1806 when the Empire was abolished. In 1814 Hanover was created a Kingdom by the Congress of Vienna in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars and the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire. Although the British monarchs listed their Hanoverian titles among their British titles, Britain and Hanover were ruled separately and were not politically unified.

In 1920 in the reign of King George V (1910-1936) a large portion of Ireland was given its independence and only the northern counties remained united with Britain. However, this part of Ireland continued to be a constitutional monarchy with the King of the United Kingdom as to their Head of State. The Free State of Ireland was separate from Northern Ireland which was still a part of the United Kingdom.

The Free State of Ireland came to an end with The Republic of Ireland Act 1948, which came into force on April 18, 1949, the 33rd anniversary of the beginning of the Easter Rising. This act created The Republic of Ireland.

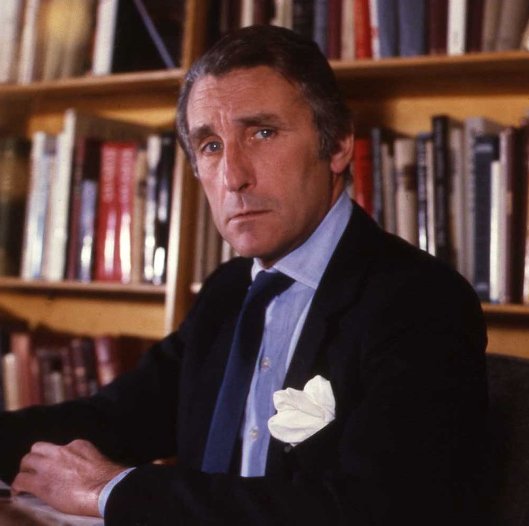

Charles III, King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Outside the Irish state, “Great Britain, Ireland” was not officially omitted from the royal title until 1953 when Elizabeth II began her reign.

Today, the official title of the King is: Charles III, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of his other realms and territories, King, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith.

Now having said my rant and given the historical background on the evolution of the title of the British monarch I must be honest and say that I do miss the traditional titles of King or Queen of England and King or Queen of Scotland. Those are in the past unless devolution comes to the UK and England and Scotland becomes independent once again. If that does happen I think we would see a return to how things were prior to 1707 when both England and Scotland shared the same monarch.