Christina (December 18, 1626 – April 19, 1689), the only surviving legitimate child of King Gustaf II Adolph of Sweden and his wife Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg, reigned as Queen of Sweden from 1632 until her abdication in 1654.

Queen Christina of Sweden’s ancestry.

Her mother was Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg (1599-1655) who was was the daughter of Johann Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, and Anna, Duchess of Prussia,

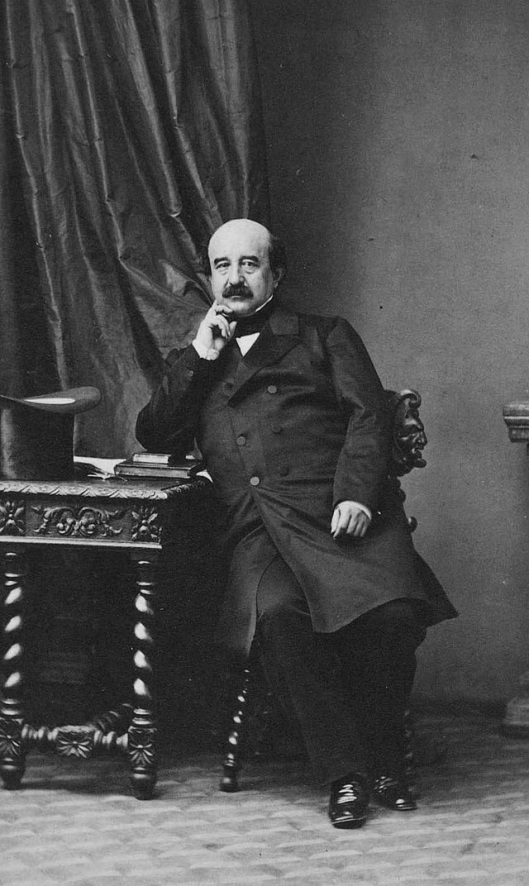

Maternal grandparents: John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg was the son Joachim III Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg, and his first wife Catherine of Brandenburg-Küstrin.

Anna, Duchess of Prussia was the daughter of Albert Friedrich Duke of Prussia and Marie Eleonore of Cleves.

Her father was King Gustaf II Adolph of Sweden (1594-1632) the son of King Carl IX of Sweden and and his second wife, Christina of Holstein-Gottorp.

Paternal grandparents: King Carl IX of Sweden was the youngest son of King Gustaf I of Sweden and his second wife, Margaret Leijonhufvud.

Christina of Holstein-Gottorp was the daughter of Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, and Christine of Hesse.

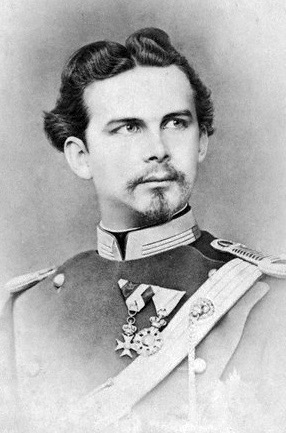

King Gustaf II Adolph of Sweden

In 1616, the 22-year-old Gustaf II Adolph of Sweden started looking for a Protestant bride. He had since 1613 tried to get his mother’s permission to marry the noblewoman Ebba Brahe, but this was not allowed, and he had to give up his wishes to marry her, though he continued to be in love with her. He received reports with the most flattering descriptions of the physical and mental qualities of the beautiful 17-year-old princess Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg. Elector Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg was favorably inclined towards the Swedish king, but he had become very infirm after an apoplectic stroke in the autumn of 1617.

Elector Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg’s determined Prussian wife, wife Catherine of Brandenburg-Küstrin, showed a strong dislike for this Swedish suitor, because Prussia was a Polish fief and the Polish King Sigismund III Vasa still resented his loss of Sweden to Gustaf II Adolph’s father Carl IX.

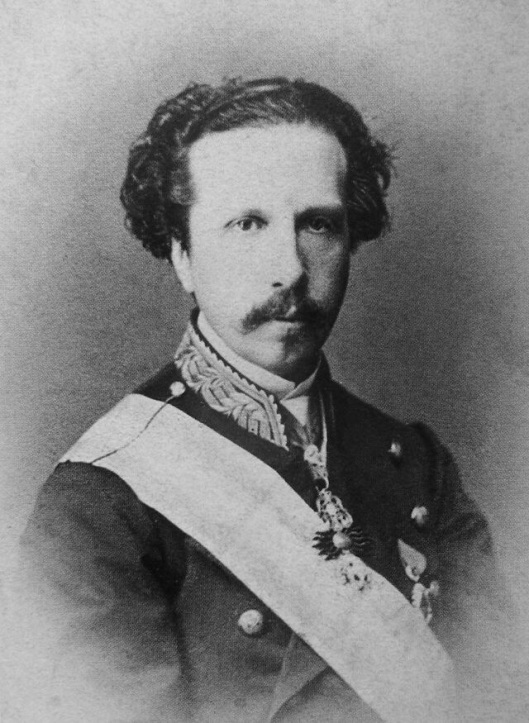

Maria Eleonora had additional suitors in the young Willem II, Prince of Orange, Wladislaw Vasa of Poland, Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg and even the future Charles I of England. Maria Eleonora’s brother Elector Georg Wilhelm was flattered by the offer of the British Prince of Wales and proposed their younger sister Catherine (1602–1644) as a more suitable wife for the Swedish king.

Maria Eleonora, however, seems to have had a preference for Gustaf Adolph. For Gustaf Adolph it was a matter of honour to acquire the hand of Maria Eleonora and none other. He had the rooms of his castle in Stockholm redecorated and started making preparations to leave for Berlin to press his suit in person, when a letter arrived from Maria Eleonora’s mother to his mother.

Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg

The Electress Anna demanded in no uncertain terms that the Queen Dowager Christina should prevent her son’s journey, as “being prejudicial to Brandenburg’s interests in view of the state of war existing between Sweden and Poland”. Her husband, she wrote, was “so enfeebled in will by illness that he could be persuaded to agree to anything, even if it tended to the destruction of the country”. It was a rebuff that verged on an insult.

The Elector Johann Sigismund, Maria Eleonora’s father, died on December 23, 1619, and the prospect of a Swedish marriage seemed gone with him. In the spring of 1620, however, stubborn Gustaf Adolph arrived in Berlin. The Electress Dowager maintained an attitude of reserve and even refused to grant the Swedish king a personal meeting with Maria Eleonora. All those who were present, however, noticed the princess’s interest in the young king.

Afterwards, Gustaf Adolph made a round of other Protestant German courts with the professed intention of inspecting a few matrimonial alternatives. On his return to Berlin, the Electress Dowager seems to have become completely captivated by the charming Swedish king. After plighting his troth to Maria Eleonora Gustaf Adolph hurried back to Sweden to make arrangements for the reception of his bride.

The new Elector, Georg Wilhelm who resided in Prussia, was appalled when he heard of his mother’s independent action. He wrote to Gustaf Adolph to refuse his consent to the marriage until Sweden and Poland had settled their differences. It was the Electress Dowager, however, who, in accordance with Hohenzollern family custom, had the last word in bestowing her daughter’s hand in marriage. She sent Maria Eleonora to territory outside of Georg Wilhelm’s reach and concluded the marriage negotiations herself.

Queen Christina of Sweden

The wedding took place in Stockholm on November 25, 1620. A comedy was performed based on the history of Olof Skötkonung. Gustaf Adolph – in his own words – finally “had a Brandenburg lady in his marriage bed”. Anna of Prussia actually stayed with her daughter in Sweden for several years after the marriage.

Within six months of their marriage, Gustaf Adolph left to command the siege of Riga, leaving Maria Eleonora in the early stages of her first pregnancy. She lived exclusively in the company of her German ladies-in-waiting and had difficulty in adapting herself to the Swedish people, countryside and climate. She disliked the bad roads, sombre forests and wooded houses, roofed with turf. She also pined for her husband. A year after their wedding she had a miscarriage and became seriously ill.

In the autumn of 1623 Maria Eleonora gave birth to a daughter, named Christina, but the baby died the next year. At that time, the only surviving male heirs to the Swedish throne was the hated Vasa King Sigismund III of Poland and his sons. With Gustaf Adolph risking his life in battles, an heir to the throne was anxiously awaited. In the autumn Maria Eleonora was pregnant for a third time. In May 1625 she was in good spirits and insisted on accompanying her husband on the royal yacht to review the fleet.

There seemed to be no danger, as the warships were moored just opposite the castle, but a sudden storm nearly capsized the yacht. The queen was hurried back to the castle, but when she got there she was heard to exclaim: “Jesus, I cannot feel my child!” Shortly afterwards the longed-for son was stillborn.

Birth of Christina

With the renewal of the war with Poland, Gustaf Adolph had to leave his wife again. It is likely that she gave way to depression and grief, as we know she did in 1627, and it is probably for this reason that the king let his queen join him in Livonia after the Poles had been defeated in January 1626. By April, Maria Eleonora found she was again pregnant. No risks were taken this time and the astrologers predicted the birth of a son and heir. During a lull in the warfare, Gustaf Adolph urried back to Stockholm to await the arrival of the baby. The birth was a difficult one.

On December 18, a baby was born with a fleece (lanugo), which enveloped it from its head to its knees, leaving only its face, arms and lower part of its legs free. Moreover, the baby had a large nose and was covered with hair. Thus, it was assumed the baby was a boy, and so the King was told. Closer inspection, however, determined that the baby was a girl. Gustaf Adolph’s half-sister Catherine informed him that the child was a girl. She “carried the baby in her arms to the king in a condition for him to see and to know and realise for himself what she dared not tell him”. Gustaf Adolph remarked: “She is going to be clever, for she has taken us all in.”

His disappointment did not last long, and he decided that she would be called Christina after his mother. He gave orders for the birth to be announced with all the solemnity usually accorded to the arrival of a male heir. This seems to indicate that Gustaf Adolph, at the age of 33, had little hope of having other children. Maria Eleonora’s state of health seems to be the most likely explanation for this. Her later portraits and actions, however, do not indicate that she was physically fragile.

Shortly after the birth, Maria Eleonora was in no condition to be told the truth about the baby’s gender and the king and court waited several days before breaking the news to her. She screamed: “Instead of a son, I am given a daughter, dark and ugly, with a great nose and black eyes. Take her from me, I will not have such a monster!” She may have suffered from a post-natal depression. In her agitated state, the queen tried to injure the child.