Tags

Archduchess Anna of Austria, Archduke of Austria, Duke Albert V of Bavaria, Elisabeth of Austria, Elizabeth of Luxembourg, Hungary and Croatia, Jagiellon Dynasty, King Albrecht II of the Romans (Germany), King Casimir IV of Poland, King François I of France, King Vladislaus II of Bohemia

Anna of Austria (July 7, 1528 – October 16, 1590), a member of the Imperial House of Habsburg, was Duchess of Bavaria from 1550 until 1579, by her marriage with Duke Albrecht V.

Family

Born at the Bohemian court in Prague, Anna was the third of fifteen children of Emperor Ferdinand I (1503–1564) from his marriage with the Jagiellonian princess Anna of Bohemia and Hungary (1503–1547) who was the oldest child and only daughter of King Vladislaus II of Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia (1456–1516) and his third wife Anne of Foix-Candale. King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia was her younger brother.

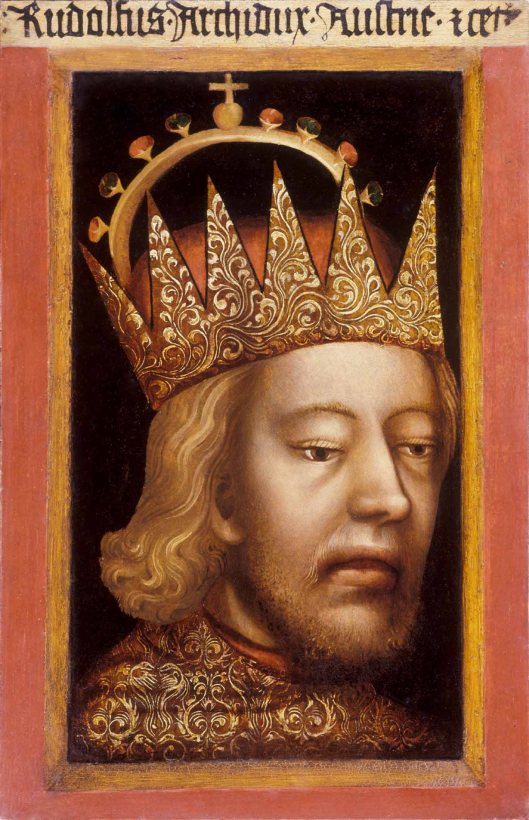

Her paternal grandparents were King Casimir IV of Poland (of the Jagiellon dynasty) and Elisabeth of Austria, the daughter of Albrecht II, King of the Romans/Germany, Archduke of Austria, and his wife Elizabeth of Luxembourg.

At the time of her birth her father Ferdinand was not yet the Holy Roman Emperor but he was King of Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia from 1526, and Archduke of Austria from 1521 until his death in 1564. Before his accession as Emperor, he ruled the Austrian hereditary lands of the House of Habsburg in the name of his elder brother, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Her siblings included: Elizabeth, Queen of Poland, Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria, Catherine, Queen of Poland, Eleanor, Duchess of Mantua, Barbara, Duchess of Ferrara, Charles II, Archduke of Inner Austria and Johanna, Duchess of Tuscany.

Anna’s paternal grandparents were Philipp of Austria, Duke of Burgundy (King Felipe I of Castile) and his wife Queen Joanna of Castile. Her maternal grandparents were King Vladislaus II of Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia and his third wife Anne of Foix-Candale.

Life

Young Anna was engaged several times as a child, first to Prince Theodor of Bavaria (1526–1534), the eldest son of Duke Wilhelm IV of Bavaria then to Charles d’Orléans (1522–1545) the third son of King François I of France and Claude of France.However, both died at a young age.

Archduchess Anna finally married on July 4, 1546 in Regensburg at the age of 17, Prince Albrecht of Bavaria the younger brother of her first fiancé. The wedding gift was 50,000 Guilder. This marriage was part of a web of alliances in which her uncle Emperor Charles V hoped to secure Duke Wilhelm’s support before embarking on the Schmalkaldic Wars. Indeed, Duke Wilhelm IV, though he remained formally neutral, granted the passage of Imperial troops to march against the forces of the Schmalkaldic League which besieged the Ingolstadt fortress.

After their marriage, the young couple lived at the Trausnitz Castle in Landshut, until Albrecht became Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria upon his father’s death on March 7, 1550. At the Munich Residenz, Anna and Albert had great influence on the spiritual life in the Duchy of Bavaria, and enhanced the reputation of Munich as a city of art, by founding several museums and laying the foundations for the Bavarian State Library.

Anna and Albrecht were also patrons to the painter Hans Muelich and the Franco-Flemish composer Orlande de Lassus. In 1552, the duke commissioned an inventory of the jewelry in the couple’s possession. The resulting manuscript, still held by the Bavarian State Library, was the Jewel Book of the Duchess Anna of Bavaria and contains 110 drawings by Hans Muelich.

A religious woman, Anna made extensive donations to the Catholic abbey of Vadstena in Sweden and generously supported the Franciscan Order. She also provided a strict education of her grandson, the later Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria.

When her husband died on October 24, 1579 and was succeeded by his eldest surviving son, Duke Wilhelm V of Bavaria, with Anna as duchess dowager maintained her own court at the Munich Residenz. 150 years after her death in 1590, her descendant Elector Charles I of Bavaria used her marriage treaty with Duke Albrecht V as a pretext to claim the Austrian and Bohemian crown lands of the Habsburg monarchy.